Support resilient, prosperous and liveable cities and towns

| 6.1 | Increase resilience to changes in climate and water availability in Greater Sydney and the Lower Hunter |

| 6.2 | Work collaboratively with local water utilities to reduce risks to town water supplies |

| 6.3 | A new Town Water Risk Reduction Program |

| 6.4 | Continue to deliver the Safe and Secure Water Program |

| 6.5 | Continue to work with suppliers of drinking water to effectively manage drinking water quality and safety |

| 6.6 | A new state-wide Water Efficiency Framework and Program |

| 6.7 | Proactive support for water utilities to diversify sources of water |

| 6.8 | Investigate and enable managed aquifer recharge |

| 6.9 | Promote and improve Integrated Water Cycle Management |

| 6.10 | Enable private sector involvement in the NSW water sector |

| 6.11 | Foster the circular economy in our cities and towns |

Our aspiration

NSW towns and cities are resilient to changes in water availability, extreme drought and flood events, with water management underpinning secure employment, a healthy natural environment and liveable places that support community health and wellbeing.

Key challenges and opportunities

Water is a finite resource that is essential to life. Water management in our cities and towns affects people’s health and wellbeing, and the amenity of communities. Many businesses also depend on water being available, reliable and safe for their operations. However, climate variability and change pose risks to sustainable water supplies as NSW caters for a growing population.

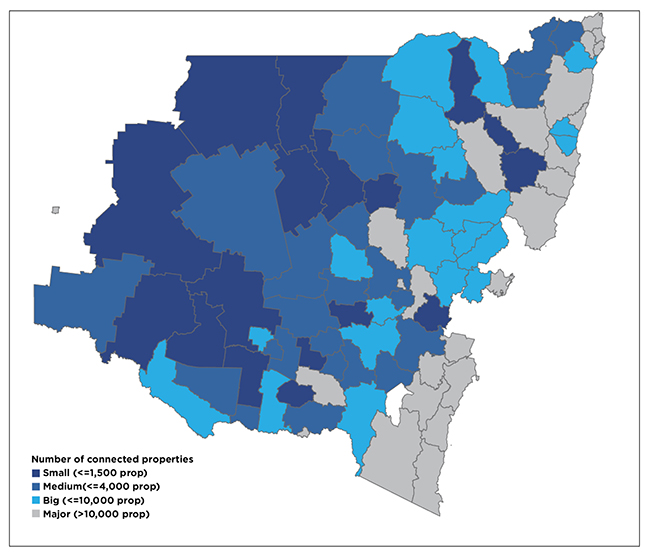

There are 92 local water utilities across NSW providing water supply and sewerage services to around two million people. There is potential for the resilience of some regional cities and towns to be at risk if these utilities fail to rise to emerging challenges. Currently, there are significant service risks across the sector, particularly in relation to water quality and security, and risk management and performance is variable. If not addressed, these risks could have substantial health and economic impacts on regional communities. We need to ensure that we improve organisational arrangements to support regional utilities and regional communities.

Councils are responsible for providing water services and operate and own associated assets. However, when councils face acute risks, such as water shortages or water quality incidents, the need for rapid intervention is triggered.

For Greater Sydney—the nation’s largest economic centre - the challenge of accommodating an estimated 1.7 million additional people by 2036 will require a medium- term response that is not ‘business as usual’.

We must put water at the heart of planning for our towns and cities. We need to improve how we plan for and manage land use, stormwater and water in the landscape to improve liveability. This includes addressing threats such as flood risks to communities and intensifying urban heat, and having water available for additional greening, cooling and amenity. We need to be thinking about innovative approaches for existing towns and cities, as well as new developments.

Across NSW, there are opportunities to increase the resilience of our cities and towns to greater climate variability and change, and to resource constraints, while generating significant economic, employment and social benefits.

Improve the liveability and resilience of our cities

NSW metropolitan areas require adequate water supplies that are resilient to drought, provide long-term security to serve growing populations and meet changing business and industry needs.

The management of wastewater from households and businesses to protect public health and waterways is a less visible, but fundamental, part of urban water management. More recently, water has been recognised as essential to maintain the liveability and amenity of our towns, cities, suburbs and neighbourhoods.

Climate change means that NSW will confront more frequent and more severe droughts, temperature and storm events. Over the next two decades, towns and cities should aim to transition to more secure water storage options, diversify water sources and increase the proportion of non-rainfall dependent sources. At the same time, we should invest in more efficient and valued uses of water by households and industry. We will also need to better integrate the way that we capture, provide and manage urban water through land use planning and urban design.

Resilient cities will require communities to be served by multiple water sources that are fit for their intended uses. Treatment at multiple points and multiple points of redundancy in the water supply, distribution and treatment systems will ensure that customers continue to receive water in the event of asset failure, environmental threats or water quality incidents.

A range of water sources will need to be drawn upon to service regional centres and urban communities, including surface water, groundwater, recycled and manufactured water (desalination and purified recycled water), as well as ongoing demand management and water conservation practices. Retaining water in the urban landscape - including through stormwater management, recycling and integrating water bodies into urban design - will enable our cities and towns to maintain the amenity of green spaces and tree canopy during drought conditions, sustain recreational areas and contribute to urban cooling. We will also need to address the implications of more severe rainfall and storm events for urban flooding, as well as for the reliability and recovery of water and wastewater systems in the face of such extreme events.

Greater Sydney and the Lower Hunter

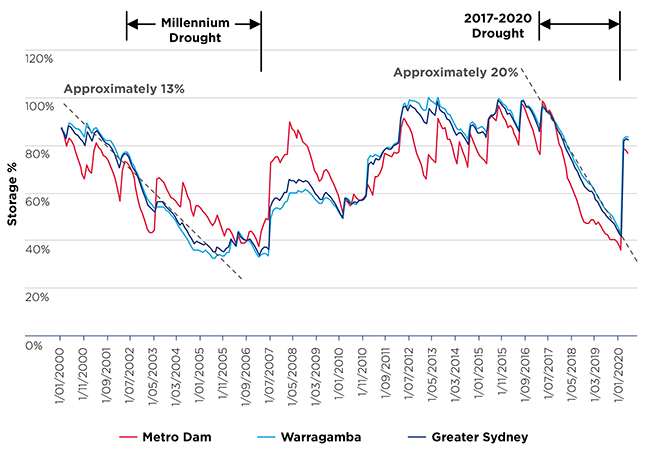

Sydney has just recovered from one of the most intense droughts on record, with storages declining by over 50% in just over two years (Figure 24). This emphasised the need for ongoing investment in water efficiency between droughts to maintain water savings, and to ensure we are planning for drought while dams are full, so we are better able to respond in the next drought.

The drought was also accompanied by bushfires that ravaged some Sydney’s major water supply catchment areas, posing an additional potential threat to the capacity of the city’s water treatment plants and the quality of drinking water.

This recent experience has highlighted the gap between supply and demand, and the vulnerability of Sydney’s water supply system to severe drought conditions. Compared to other Australian cities, Sydney has a low level of rainfall-independent water supply, as shown in Table 1.

Only the Sydney Desalination Plant (which provides around 15% of daily demand when operating at full capacity) and water recycling plants (providing up to only 8% of daily demand in Sydney and 9.6% of daily demand in the Hunter) are climate independent.

Source: WaterNSW, May 2020

| City | Desalination capacity as a % of demand | Recycling capacity as a % of total demand | Total climate independent sources as a % of total demand |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sydney | 15% | 8% | 23% |

| Melbourne | 34% | 3% | 37% |

| Perth | 45% | 4% | 49% |

| Adelaide | 38% | 11% | 49% |

Sources: Australian Water Association, Desalination Fact Sheet, Bureau of Meteorology 2021, National performance report 2019-20: urban water utilities, part A

Sydney is at a tipping point for its rainfall- dependent water supply system, with the forecast long-term yield for water now being less than the annual demand. Increasing our proportion of rainfall-independent supplies allows us to slow down depletion rates in times of drought, helps to keep our dams full (providing long-term security) and enhances our ability to respond to other shocks in the system such as water quality incidents.

The resilience of Sydney’s system can be improved immediately by increasing water conservation and water efficiency and, in the future, by securing more reliable water supplies that include additional rainfall independent sources of water - either desalination and/or recycled purified wastewater.

By 2040 Greater Sydney’s population is forecast to grow by 1.9 million to 7.1 million people and to 8.3 million by 2056. Much of this growth will be in the Western Parkland City. Centred on Wianamatta South Creek and its tributaries, planning in this catchment is taking an integrated land use and water cycle management approach to ensure there is enough water to achieve urban cooling, provide open space and sustain about two million trees. Options for recycling and stormwater harvesting to support the amenity provided by the parkland have been identified.

A growing population in Sydney will also place significant pressure on an aging wastewater network as it reaches capacity, particularly in the Eastern Harbour and Central River cities.

There is a need to invest in new assets and renew old ones, and to intercept and recycle more of Sydney’s wastewater. At present, approximately 80% of Sydney’s wastewater is treated and discharged to the ocean. In the future, there are opportunities to use water more than once on a broader scale and continue to protect our precious waterways and beaches for the future.

In the Lower Hunter, the nature of water storages means that water storage levels can fall quickly in prolonged periods of hot and dry weather, making the region vulnerable to drought. As demonstrated in the most recent drought, Hunter Water’s storage levels can go from typical to critical levels within three years. The Lower Hunter Water Security Plan will assess if the current level of water security is appropriate, or if additional measures to improve water security are needed.

To meet future demand, new sources of water will be considered alongside ongoing water efficiency and loss reduction measures. A range of water supply sources including water transfers between regions, groundwater, desalination and dams could be used to provide long-term water security and drought resilience. Expansion of recycled water and stormwater harvesting schemes offer the potential for water savings, as well as liveability and environmental benefits. The updated Lower Hunter Water Security Plan will be released in 2022 and will set out a long-term portfolio of supply and demand measures that will ensure a secure supply of water to the Lower Hunter.

Action 6.1 Increase resilience to changes in climate and water availability in Greater Sydney and the Lower Hunter

Actions | Horizon 1 | Horizon 2 | Horizon 3 | |

| The Government will release consultation drafts of the Greater Sydney Water Strategy and Lower Hunter Water Security Plan by the third quarter of 2021. After community feedback, the strategies will be finalised and implementation plans will be published. | X | |||

Reduce water service risks and increase resilience for regional towns

Local water utilities face challenging conditions, with drought, flood and climate variability all potentially affecting water availability. There is also significant variability in the geographic coverage and population trends in the areas covered by local water utilities, with service areas ranging from 285 to over 50,000 km2 while populations range from 1,000 to over 300,000. Remoteness and low population density can contribute to cost disadvantages, revenue raising challenges and skills shortages, including in specialist water engineers and operators to maintain town water infrastructure. Some regional towns also need to provide for transient tourist population peaks and water for households that are not serviced by town water during extended dry periods.

In 2018/19, local water utilities had an annual revenue of $1.51 billion and combined infrastructure current replacement costs of $28.8 billion.

Regulating local water utilities in NSW

The vast majority (89) of NSW’s local water and utilities (LWUs) are either general purpose councils, which operate as financially separate to general local council operations, or special purpose county councils. Councils exercising water supply and /or sewerage functions do so under the Local Government Act 1993. Three LWUs - Cobar Water Board, Essential Energy and WaterNSW for the Fish River Water Supply - operate as water supply authorities under the Water Management Act 2000. Central Coast Council exercises its functions under both the Local Government Act 1993 and as a water supply authority under the Water Management Act 2000.

The department is the primary regulator of all regional LWUs under the Local Government Act 1993. The Regulatory and Assurance Framework for Local Water Utilities (PDF, 1100.53 KB) supersedes the Best-Practice Management of Water Supply and Sewerage Framework. The framework sets out the department’s regulatory objectives and functions, as well as its assurance role and expectations for effective, evidence-based strategic planning. It applies to local water utilities in regional NSW and is designed to ensure risks are managed effectively and strategically. A number of other agencies, including NSW Health, the NSW Environment Protection Authority, the Office of Local Government (as general council regulator) and Dams Safety NSW, are each responsible for aspects of the regulation of LWUs.

In 2019, a comprehensive, inter-agency assessment of town water and sewage systems operated by local water utilities found significant and widespread service risks across the sector, particularly in relation to water quality and security:

- Across NSW, there are 274 town drinking water systems operated by LWUs: 161 of these systems (or 59%) are in the highest bands of water quality risk (either 4 or 5 out of 5 levels of risk), meaning critical treatment barriers or necessary drinking water quality controls are inadequate.

- Almost half (47%) of LWUs operate at least one town water supply scheme in the highest category of water security risk (level 5), meaning there is inadequate secure supply and storage to meet the consumptive needs of the community it serves.

Currently, the performance of LWUs varies, with some more advanced in achieving best practice water management and others lagging behind. Data on key performance measures for LWUs in regional NSW - including information on assets, environment, health, pricing and water - can be found on the Department’s live dashboard.

Poor risk-management by some local water utilities (LWUs) is primarily a result of shortcomings in financial sustainability, capability, strategic planning and governance due to four main causes:

- Scale and remoteness - LWUs with small or spread-out customer bases face intrinsically higher per-person costs for delivering water and sewerage services and are sometimes unable to raise the revenue needed to manage their risks through user charges alone. These utilities can also struggle to attract skilled staff because their areas lack the amenities of larger urban centres.

- Skills shortages - Some LWUs have difficulty attracting and retaining suitably qualified and experienced staff to fill critical roles within their business. In some cases this is due to shortages of certain skillsets in the market, but in other cases it is simply that LWUs cannot afford to offer competitive remuneration and opportunities for career progression. Solutions to these issues must also consider the complex regulatory requirements and industry standards that apply to local water utilities.

- Poorly targeted funding - LWUs are funded primarily through capital grants that co-fund infrastructure to address priority water and sewerage system risks. There are several issues with this approach. A key issue is that it does not fully account for differences in the capacity of utilities to fund solutions themselves through service charges. Also, targeting funding based on high priority risk can discourage utilities from taking action until risks become critical enough to be eligible for funding. Capital funding can also introduce a bias toward infrastructure solutions. It can discourage the consideration of whole-of-lifecycle cost of infrastructure and may not be a sustainable solution for utilities that require continuous funding support to be able to cover their ongoing costs, including maintaining and renewing infrastructure to an adequate standard.

- Ineffective regulatory mechanisms - Regulations aimed at ensuring robust strategic planning and governance by local water utilities have not been as effective as they could be. In part, this is the result of the Department’s lack of clarity and proportionality in its regulatory approach to overseeing and supporting local water utilities, as well as shortcomings in the transparency and accountability of its activities. Another issue is the absence of an effective mechanism for coordinating regulatory objectives and activities among co-regulators and other agencies.

It is unlikely LWUs will be able to entirely overcome these issues without changes to the existing approach to regulating and supporting the sector. Reducing the sector’s risks to tolerable levels requires a shift in the NSW Government’s approach to directly target the causes of underperformance.

Action 6.2 Work collaboratively with local water utilities to reduce risks to town water supplies

The Government will continue to work collaboratively with local water utilities to improve organisational arrangements and reduce risks to town water supply service provision, with the aim of achieving the following outcomes:

Actions | Horizon 1 | Horizon 2 | Horizon 3 | |

| X | |||

Action 6.3 Deliver a new Town Water Risk Reduction Program

The Department of Planning, Industry and Environment, in collaboration with NSW Health, the Environment Protection Authority, the Office of Local Government and Regional NSW, will implement a two-year Town Water Risk Reduction Program in partnership with councils and local water utilities. This new program will:

Actions | Horizon 1 | Horizon 2 | Horizon 3 | |

| X | |||

Continue to invest in infrastructure that delivers safe and secure water supplies to regional communities

An important step towards addressing water service risks and improving water service quality outcomes has been the implementation and re- design of the Safe and Secure Water Program - a funding program to address water security, water quality and environmental impact risks in urban water systems across regional NSW.

The re-design of the Safe and Secure Water Program (re-launched in October 2018) changed the program from an application-based program that co-funds projects to a risk-based and needs-based funding program. Under the re- designed program, the NSW Government assesses and prioritises all town water risks in urban water systems in regional NSW. Co-funding is provided to implement the best solutions to address identified risks (where the LWU agrees to co-fund), starting with the highest priority risks. Risks are prioritised based on the socio- economic circumstances of the customers of the responsible LWU, as well as service cost disadvantages experienced by the utility.

Action 6.4 Continue to deliver the Safe and Secure Water Program

Actions | Horizon 1 | Horizon 2 | Horizon 3 | |

The Government will continue to deliver the Safe and Secure Water Program, co-funding solutions to high priority water service risks and strategic service planning. The NSW Government will invest more than $500 million over the next eight years to support local water utilities reduce risks in urban water systems through the Safe and Secure Water Program. | X | X | ||

Protecting public health through drinking water quality

Access to safe drinking water is essential for good health and hygiene. People in NSW have an expectation that their drinking water is safe. It is vital that suppliers of drinking water understand and manage risks to drinking water safety in an effective and consistent way.

The national Australian Drinking Water Guidelines and Framework for the Management of Drinking Water Quality (the Framework) provide a basis for determining the quality of water to be supplied to consumers in all parts of Australia.

In NSW, the Framework is mandated through the requirement for water utilities to prepare Drinking Water Management Systems under the Public Health Act 2010 and Public Health Regulation 2012. Ongoing implementation of drinking water management systems will be a long-term task. The NSW Government is committed to ensuring that these systems are maintained and effectively implemented and that they become part of the work culture of NSW water utilities.

As drinking water management systems are embedded into the planning and operations of water utilities, focus will shift to ensuring effective review and continual improvement such as:

- identifying and assessing emerging risks to water quality, including those posed by climate variability and change

- identifying ways to improve risk management for water utilities through the Town Water Risk Reduction Program

- implementing a consistent process for external review and audit of drinking water management systems.

Action 6.5 Continue to work with suppliers of drinking water to effectively manage drinking water quality and safety

The Government will support suppliers of drinking water by:

Actions | Horizon 1 | Horizon 2 | Horizon 3 | |

| X | |||

Focus on water use efficiency

Adoption of water efficiency is one way to reduce the demand on finite water resources by a growing population in a changing environment. Water efficiency should aim to reduce day to day water use by the community without any adverse effects on basic water needs—that is, making the community more efficient and mindful about how we use water in our everyday lives.

We need to reinvigorate water use efficiency programs in our cities, towns and regional centres. While new sources of water are required for cities and towns across the state, there is also a need for increased investment in water system efficiency, water conservation and demand management to delay the timing and reduce the scale of investment in new supply infrastructure.

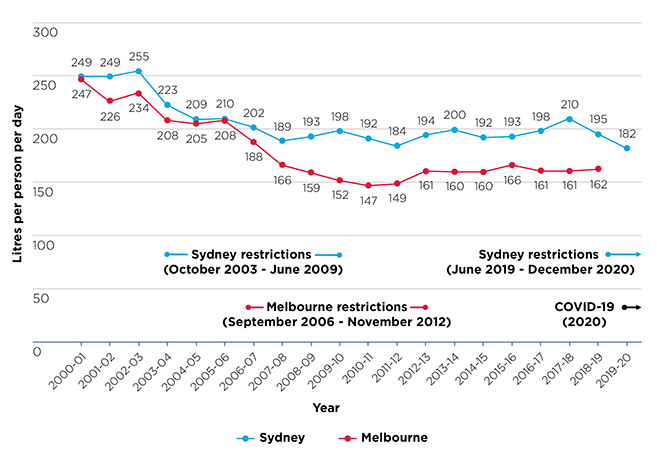

Water conservation is strongly supported by communities and businesses, and across government. By 2011, Sydney Water’s Demand Management Strategy (required at the time by Sydney Water’s Operating Licence) was saving around 120 GL/a, or around 20% of Sydney’s current annual water consumption. Water use targets had been in place since 1995 and achieved significant reductions in water use. This occurred during the Millennium Drought when there was increased investment in and focus on water conservation. However, following the end of the Millennium Drought, investment in and savings from water conservation have fallen markedly.

The introduction of the Economic Level of Water Conservation Methodology in 2016 was designed to enable Sydney Water to determine an optimal mix of water conservation activities, but has proven ineffective in maintaining the capability required to develop and drive water conservation programs, funding and savings.

An Audit Office report (2020) into water conservation in Sydney found significant failings in water conservation initiatives, particularly outside times of drought. Positive progress has been made to reduce household demand for water in Sydney over the past two years, down from 209 litres per person per day in 2017/18 to 182 litres per person per day in 2019/20 (Figure 26). The NSW Government is enhancing its investment in water conservation and IPART has recently increased the level of expenditure allowed for Sydney Water to deliver its water conservation program.

In regional NSW, there are still large discrepancies between the average residential water consumption rates in different towns. For example, the town with the highest rate of water use per household consumed approximately nine times more water than the town with the smallest rate. For more information visit our live dashboard.

The efficient use of water contributes to the sustainability of long-term supplies as populations increase and builds community resilience to drought. The role of water efficiency should have equal standing with additional supply side options when balancing supply and demand to ensure water is being used efficiently before imposing costs on the community for additional water infrastructure.

Action 6.6 A new state-wide Water Efficiency Framework and Program

The Government will implement a state-wide Water Efficiency Framework and Program for urban water in 2021 following consultation with key stakeholders, including water utilities. The framework and program will:

Actions | Horizon 1 | Horizon 2 | Horizon 3 | |

| X | |||

Use diverse water sources for greater water security

Many regional towns are dependent on a single source of water for town water supply. This makes them particularly vulnerable to drought, as well as other incidents that could compromise the availability or safety of water supplies.

Diversification of water sources—which may be across surface water and groundwater, recycling and desalination—and the use of other standards of water for non-drinking water purposes can significantly improve water security.

Stormwater and recycled water remain largely underused water sources with significant potential to improve water security for towns and communities. Options may include purified recycled water for drinking. Recycled water also provides options for supplying fit-for-purpose water for industry and agriculture, and for maintaining ‘green’ spaces—reducing reliance on drinking water supplies and relieving the pressures on the wastewater system.

A number of issues need to be examined and resolved regarding the regulation and governance of stormwater harvesting including the relationship with water sharing plans.

This is particularly important in areas that are transitioning from rural to urban landscapes. The Government will work to clarify regulatory arrangements and develop guidelines to make these types of options easier to progress, where they are appropriate.

Stormwater harvesting: a successful venture for Orange

By August 2008, Orange was in the midst of a critical water shortage as a result of the Millennium Drought. Water storages had dropped below 26.7% (Cooperative Research Centre for Water Sensitive Cities 2018, Case Study: Orange Stormwater to Potable: Building urban water supply diversity, p.11). At the time, inflows to storages on the outskirts of town were not enough to meet demand and few alternative supplies were available. Urban stormwater harvesting was identified as one solution to meet this shortfall.

Blackmans Swamp Creek and Ploughmans Creek stormwater harvesting schemes now operate in urban creek catchments. The schemes capture a portion of the high creek flows during storm events and transfer these into the nearby Suma Park Dam, where the water is then treated according to the Australian Drinking Water Guidelines.

Treated stormwater has the potential to supply over 25% of Orange’s water demand and this alternative water supply has improved the city’s resilience to drought.

The Government has heard that many local water utilities want to progress options for purified recycled water, but need government support to work with the community to increase understanding and acceptance of the concept.

The Government has also examined the economic regulatory barriers to cost effective water recycling, including a review by Infrastructure NSW in 2018. The Greater Sydney Water Strategy (Action 6.1) will include policy changes in the areas of planning, water conservation and environmental management to address barriers to cost efficient water recycling, including:

- developing strong policy signals for the support of cost-effective water recycling

- reviewing planning instruments and charges

- supporting the early consideration of water recycling as a possible option for water servicing strategy in land use planning for growth areas

- determining the efficacy of BASIX to support water recycling

- reviewing developer charges

- initiating public engagement for consideration of purified recycled water for drinking.

Action 6.7 Proactive support for water utilities to diversify sources of water

Actions | Horizon 1 | Horizon 2 | Horizon 3 | |

The Government will support water utilities to diversify sources of water including groundwater, stormwater harvesting and recycling. This will include progressing relevant regulatory reform and community acceptance campaigns to help increase the uptake of diverse water sources with the potential to increase water security and resilience for towns and communities. | X | X | ||

Managed aquifer recharge

One solution that is proving successful in other states and overseas is managed aquifer recharge (MAR). The basic idea of MAR is to use below- ground aquifers to temporarily store water instead of above-ground reservoirs. The aquifer acts as a water bank. Water enters the aquifer via infiltration ponds or injection wells during times of plenty, and is later redrawn using bores during times of scarcity. As well as smoothing out demand versus supply, water that would have otherwise evaporated becomes available.

In Australia, MAR schemes have typically been developed to support community water supply (such as in Perth). Some countries have used them to increase water security for agricultural or industrial sectors (for example, Spain). They can be of different sizes: from small-scale storage of stormwater by a council to significant diversions of surface water by an irrigation corporation to large-scale government-owned schemes (such as Perth’s MAR scheme).

MAR comes with technical challenges: there must be water available for diversion; the diverted water and host groundwater must be of compatible qualities; the aquifer must be suitable - with sufficient storage while not allowing the water to flow into other areas; and any environmental impacts must be fully understood.

In NSW, we are in the early stages of investigating MAR as an option for improving town water security and to possibly support the agricultural sector. There are some things we need to understand better to understand the feasibility of MAR in NSW. These include:

- its economic viability for different uses - the expense of temporarily storing water must be less than the economic return made from later use

- how to fairly distribute the benefits between groundwater and surface water users, and among surface water users with and without access to MAR

- the impact of increased storage being available within a cap and trade water management framework (including the Basin Plan sustainable diversions limits)

- impacts on surface and ground water quality, connectivity and the environment - including impacts to Groundwater Dependent Ecosystems.

Despite the challenges, MAR has the potential to be a significant opportunity for innovative water management in NSW, with benefits for town water security and possibly the agricultural industry.

Action 6.8 Investigate and enable managed aquifer recharge

The Government will develop a policy that sets out the framework for MAR in NSW and identify where it is technically and economically viable. We will:

Actions | Horizon 1 | Horizon 2 | Horizon 3 | |

| X | X | ||

Take an integrated water cycle management approach for urban planning

Integrated Water Cycle Management is a key element of urban water reform in the National Water Initiative. Integrated water cycle management captures opportunities to improve all aspects of water management and provide urban amenity as part of the design and establishment of new urban communities, urban infill and urban redevelopment. It is also relevant to the replacement and renewal of existing urban infrastructure, including water and wastewater systems, channels and drainage lines, as well as footpaths and roadways.

An integrated water cycle management approach promotes the coordinated development and management of water with land, other infrastructure and related resources to facilitate protection of the water resource and vital ecosystems, and deliver place-based, community-centred outcomes that maximise the resilience and liveability of cities and towns. This coordinated approach allows a greater range of options to be identified and evaluated to enhance urban amenity and achieve better economic value from infrastructure investment.

Critically, integrated water cycle management fosters consideration of the urban water cycle early in the urban planning process, and recognises the role that water plays in creating places that contribute to community health and wellbeing.

In 2018, the NSW Government accepted Infrastructure NSW’s advice that improvements need to be made in integrated water resource planning to prioritise major water infrastructure investment decisions to meet the challenges facing a rapidly growing Sydney. The South Creek Sector Review by Infrastructure NSW identified that a more integrated approach to water cycle and land use planning could generate significant economic benefit (~$6.5 billion NPV by 2056) for the Western Parkland City.

One of the key challenges is to identify the best mix of supply and demand options. This includes leveraging the significant reinvestment required in wastewater systems to ensure that the most economic and affordable investment decisions are made. An integrated water cycle management approach requires robust, place- based, economic and engineering options analysis. It also requires appropriate policy, regulatory and planning control settings to achieve the desired outcomes.

The Greater Sydney Water Strategy and the Lower Hunter Water Security Plan (Action 6.1) will take an integrated water cycle management approach to identify optimal investment portfolios, ensure that the investment required is affordable and that the policy settings for water cycle management support long-term strategic planning for these areas.

Local water utilities currently undertake integrated water cycle management planning. As part of the Town Water Risk Reduction Program (Action 6.3), the Government will be work with councils to revamp their approaches to integrated water cycle management.

Action 6.9 Promote and improve Integrated Water Cycle Management

Actions | Horizon 1 | Horizon 2 | Horizon 3 | |

The Government will promote Integrated Water Cycle Management through the NSW planning system and through water management arrangements. All regional and metropolitan water strategies are developed based on an integrated water cycle management approach. | X | X | ||

Integrated Water Cycle Management: the key to a cooler city

Heatwaves are responsible for more deaths in Australia than any other disaster (Australia’s deadliest natural hazard. The Conversation, 2018), and as urbanisation continues, the heat island effect will become more pronounced unless planning includes green spaces to mitigate this effect. Sydney is forecast to reach temperatures of 50°C by 2040 if urban heat is not addressed.

The cooling effect of canopies and green space will become increasingly important to Sydney’s liveability and amenity—particularly in the west of the city where the ameliorating effect of coastal sea breezes is not felt.

The success of the Western Parkland City will require more water, particularly during the establishment of parks and gardens. Its design will also be oriented towards water in the urban landscape, either by lakes and water features amongst the parklands or by Wianamatta South Creek itself as a healthy urban waterway sustained and protected by the sensitive management of urban stormwater and wastewater.

See the case study about Wianamatta South Creek in section 4.

Private sector involvement to facilitate innovation and competition in the water sector

In 2006, NSW was the first state to allow private companies to build and operate recycled water and sewerage schemes under the Water Industry Competition Act 2006. The Act facilitates competition and innovation in the supply of water and wastewater services by setting up a licensing framework for private companies that wish to provide drinking water, recycled water and/or sewerage services to residential, commercial and industrial customers.

There are now 22 private water and sewerage schemes in the Greater Sydney and Hunter regions, providing services to over 6,000 water customers and 8,000 sewerage customers (as at June 2019). They range from schemes servicing greenfield residential developments in outer Sydney and the Lower Hunter, to innovative water recycling schemes in award-winning urban revitalisation projects like Central Park and Barangaroo.

To ensure that the Act continues to support innovation and competition, the Government will streamline the licensing process and reduce costs and delays for industry. Key reforms will focus on regulating high risk schemes, removing barriers to entry, separating the licensing of operators and retailers from the approval of individual schemes, and strengthening customer protection and last resort arrangements.

These reforms will ensure that cities and towns have options to identify the preferred solution to their water servicing needs, whether that is provided by government-owned utilities or the private sector.

Action 6.10 Enable private sector involvement in the NSW water sector

Actions | Horizon 1 | Horizon 2 | Horizon 3 | |

The Government will finalise reforms to the Water Industry Competition Act 2006 and Water Industry Competition Regulation to support involvement of the private sector in the supply of water and wastewater services. | X | |||

Resource recovery in cities and towns

In urban areas, water utilities typically manage both water and wastewater. Pumping water and treating wastewater are very energy intensive.

Every decision about the source, treatment and distribution of water and wastewater has significant implications for energy and chemical requirements, and the waste streams generated. Actions to optimise the efficiency of distribution and treatment systems can have a significant impact on operating costs, while opportunities to reduce energy demands can reduce their overall carbon footprint.

Urban water management presents significant opportunities for energy and resource recovery - both for the water utility itself and for the communities that it services. In addition to providing recycled water, wastewater can be treated in a way that creates heat or methane, while nutrients and carbon can be recovered for use as fertiliser and other more advanced purposes. Cities and major regional centres have an increasing interest in the co-digestion of wastewater with other food and organic waste streams. This creates renewable energy and reduces the amount of food waste going to landfill. Reservoir and treatment plant sites are often highly suitable for solar energy capture, while the hydraulics of water and wastewater systems provide opportunities for mini hydro power generation.

Commitments to net zero emissions, resource scarcity and increases in energy and waste management costs are driving research and investment in the ‘circular economy’ as it applies to the water industry. Communities also support and expect water utilities to innovate and invest in optimising their energy use and resource recovery.

Action 6.11 Foster the circular economy in our cities and towns

Actions | Horizon 1 | Horizon 2 | Horizon 3 | |

The Government will partner with councils, water utilities, research organisations, the private sector and communities to pilot innovative urban water management that improves resource efficiency and recovery, and contributes to working towards a net zero emissions future. | X | X | X | |